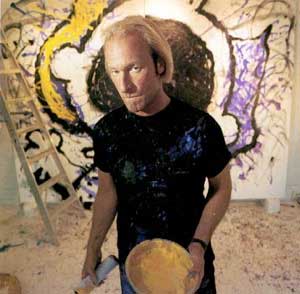

TOM EVERHART PAINTS like an over-caffeinated aerobics instructor. Leaping, pummeling, gyrating and contorting, Everhart hurls purple gobs of pigment onto a 14-foot-long canvas inside his Mt. Vernon studio with a grim-faced intensity. Wafting through the whitewashed rooms is a noxious-seeming, turpentine-like order, and Everhart apologizes-it’s from a chemical he adds to his acrylic enamels and oils to speed up drying. “I’m sure the stuff isn’t good for you, Everhart jokes, “but I can’t blame my cancer on it.”

More than an hour later, the roller reduced to fibrous mush, Everhart surveys his work while massaging his throbbing right arm. He’s done: Tonight, the first color of Sally’s multi-hued hair has been put down. Sally, as in the cartoon character from Charles Schulz’s Peanuts comic strip. EVERHART’S THE FIRST TO ADMIT HIS PAINTINGS ARE ridiculous. Huge, sprawling depictions of the Peanuts gang, they’re all done in perverse close-up, with an intentional in-your-face bigness that dwarfs the viewer. Like the eight-foot-long Snoopy, puckering his bee-stung lips suggestively; or its companion piece, a seven-foot-tall Lucy, horrified at being smooched by a pooch, titled “I’ve Been Kissed By Dog Lips!!, or the eight-foot-tall Peppermint Patty - disappearing under cyclonic swirls of big hair, inspired by Baltimore ‘dos, Everhart claims. To reinforce that ridiculousness, Everhart paints with the most ordinary of objects he can, everything from spatulas to tampons. In the end, there’s not a hint of angst or didacticism in any of his works, and that’s exactly how Everhart intends them. “Then world’s losing its sense of humor,” explains Everhart. “People don’t smile anymore. So I’m not going to create paintings with a heavy message-people get enough of that in real life.”

Not bad for a guy who was written off by doctors as a dead man walking. Because eight years ago, Everhart was diagnosed with advanced liver and colon cancer, an insidious combo that almost always proves fatal; he was given less than 24 months to live. But while laying in a Mercy Hospital recovery room following a second surgery, to remove a tumor the size of a banana from his colon, Everhart had a vision. Until then, he specialized in painting lush garden landscapes on the side. As one of a handful of artists authorized to draw Schulz’s characters, Everhart did commercial renderings of the Peanuts gang-MetLife ads, Franklin Mint commemorative plates. Everhart's uncanny depiction of Schulz’s comics had so impressed the the 65-year-old cartoonist that the two quickly formed a close friendship. As a get-better gesture, a concerned Schulz-or “Sparky,” as everyone called him-had sent his protégé a stack of Peanuts strips to cheer him. Everhart piled them at his hospital bedside, next to a collection of art-history books. One day, as light shimmering in for the windows melded with the kaleidoscopic colors in nearby get well flowers, a pain racked Everhart saw images of artistically rendered Peanuts characters flickering on the walls. All of the as interpreted by artists, like Claude Monet, David Hockney, Edvard Munch, Willem de Kooning. It was Peanuts seen through the prism of art history.

TOM EVERHART LOVES artifice. So don’t expect his third-floor apartment, in a starchy Victorian brownstone just one floor above his studio, to be an antiseptic loft crusted with paint and littered with dumpy, starving-artist furniture. Instead of crafting the obligatory artist’s dive, Everhart gutted and overhauled the space he discovered two years ago – and still rents – to create a sophisticated bachelor’s retreat filled with an eclectic mishmash of over the top furnishings. There are two overstuffed sofas in satiny flower-and-stripes upholstery. A Grecian-statue lamp with a leopard shade. Mirrors framed in heavy rococo gilt. Crystal goblets filled with Hershey kisses, cake stands with pyramids of apples, soft-faded oriental rugs layered atop one another. Window valances made from hanging bouquets of dried roses. Everywhere-on lampshades, ottomans, armchairs – there are yards and yards of fringe Everhart attached with a glue gun. And in the exposed kitchen, with its stacks of Fiestaware and antique china, weirdly realistic plastic food - a Cobb salad and udon soup, purchased in Tokyo on a tip from John Waters – sits on the rarely used stove. “Doesn’t this feel like Paris?” Everhart asked with a grin, stirring his coffee and gazing out the kitchen window at trees just starting to leaf. Up close like this, Everhart’s perma-tan seems deeper, his white-blonde hair in its Prince Valiant cut even lighter. “I get tan really easily now since chemotherapy,” Everhart explains, “and my hair really bleaches out, even if I’m just riding in my Jeep. Chemo does some really weird stuff.” Especially to Everhart’s paintings, from his undergrad and grad-school days at Yale to his subsequent stint in New York, Everhart was committed to perfecting his technique of dreamily hypnotic garden landscapes, with their Impressionistic colors of lavender, periwinkle, and moss. But disillusioned after just six months with the Big Apple’s frenzied pace and constant distractions, Everhart headed in 1981 to Baltimore. He was somewhat familiar with the city (he had spent his growing-up years partially in San Francisco, partially in Washington, D.C.) and was especially enchanted with its unpretentiousness and saner pace. Settling in on Read Street, Everhart hit the market at a fortuitous time: It was the art boom of the go-go ‘80’s and his soothing compositions appealed to a big-spending corporation eager for showpieces. Soon his landscapes were going for $20,000 a pop, and he opened a satellite studio in Santa Monica to tap into California’s lucrative clientele base. Over the next 15 years, Everhart moved around the city, to Roland Park and Canton and back to Mt. Vernon, and continued with his hugely successful pastel landscapes – those were his works of the coffee mugs and shopping bags that advertised the opening of Towson Town Center. But stagnancy was creeping into his work, and he was getting artistically restless. “I knew that there was another side I was trying to get to, but I never found it,” Everhart recalls. “And it was really through this relationship with Sparky, and the moment in the hospital that it all started happening.” “It” HAS BESTOWED A CELEBRITY CACHET on Everhart. He’s a fixture on the local art sense, known for popping up at the city’s trendiest galleries and charity bashes, and was recently ranked by this magazine as on the city’s sexiest guys. Gregarious, laid back, and always dressed in at least on article of paint-splotched clothing, Everhart with his black-clad retinue, does the circuit of hip hotspots: Lately, brunch has been at the Mt. Vernon Donna’s, where Everhart noshes on vegetarian eggs Benedict, and dinners are often next door in the darkened corners of its sister restaurant, The Ruby Lounge, Everhart’s kitchen-away-from-home. For drinks, it’s usually the Club Charles, where Everhart is known for bringing his own teacup. Everhart is also known for being heavily invested in bolstering the Mt. Vernon community, which at times seems more of a small town than a big-city neighborhood. Concerned that Donna’s, which features rotating artwork on its walls, wasn’t promoting locals enough, Everhart struck a deal: If the restaurant would agree to hang pieces by students from the Maryland Institute, College of Art and the Baltimore School for the Arts, he would loan his works to the Ruby Lounge. Diners were soon nibbling black-bean hummus under the enormous painting of Sally screaming with open-mouthed gusto. Everhart also donated his talents to the Downtown Partnership’s May Day celebration, by painting a psychedelic flower gamboling down a two-block section of Charles Street. The scene, with Everhart wielding a paint sprayer and dodging traffic, was vintage Mt. Vernon- everyone who knew him, from a dread-locked poodle-walker to a mom in denim overalls, came by to say hello. But although people in town know Everhart, few seem to know much about him. Maybe it’s partially because, until recently, a longtime girlfriend and a studio drew him two weeks a month to London, which he still visits frequently in order to develop ties with European and Asian collectors. Maybe it’s also because Everhart seems to actively cultivate a mystique: Close lipped about his upbringing and background, he prefers to deflect questions back to his artwork. It seems that Everhart – much like pop artist and household name Andy Warhol – has learned that advantages of selective information to creating a public persona. But when the inevitable comparisons between Warhol’s work, with its soup cans and Superman comics, are made with his own, Everhart is quick to debunk any similarities. “Warhol takes an American popular culture piece and presents it as that, as an icon.” Everhart explains between bites of fruit tart and sip of coffee, “My works aren’t icons. Like the series I’ve done of Snoopy’s doghouse – the paintings are done much like Monet would do his cathedrals. It’s not about a doghouse; it’s about the structure outside changing in time.” “Series” is Everhart’s latest buzzword. His frequent dinner guests and visiting clients can glimpse that firsthand in his apartment, with its Peanuts gallery on the walls. The works Everhart had hung-the portrait of the be-wigged Peppermint Patty, Snoopy doghouse captured in burnt reds and oranges, Schroeder’s top piano-are all parts of series-in-progress. Everhart’s hoping to build up the body of his work by doing numerous variations on a single theme, aiming for impact when the pieces go to museums. “One hairdo is funny,” Everhart declares, “but if you walk into a museum and 12 weird hairdos are staring at you, well...“ For Everhart, repetition heightens the ridiculousness, especially for the next series he’s planning: toasters, the clunky, and ‘50’s kinds Schulz features in the comic strip. He’s hoping to do six toaster canvases – maybe take about six months to complete. If it seems risky for an artist who not that long ago battled one of the deadliest forms of cancer to plan such ambitious work, Everhart doesn’t show it. So far, he has no intention of downsizing either the scope of his series or its scale - or, slowing down the work that comes to him when he was at his sickest. “I have no desire to leave this work right now,” Everhart explains, glancing up at the gang of Peanuts characters that share his apartment walls. “The only problem,” he says softly-maybe referring to his over-jammed schedule, maybe to the fear that his cancer may reappear –“is finding enough time to do it.” By Kathleen Renda for Baltimore Magazine |

Wordlessly, the 43-yer-old Everhart explodes into dervish of frenetic motion, cranking up Brahms’s Symphony No.4 to a deafening decibel and attacking the canvas. He whuumps it with a hardware-store paint roller, as if he were beating a rug; savagely squiggles it with his fingerprints; smears it what the sleeve of his black turtleneck. Stray droplets of purple sail onto the ceiling and floor. Everhart is zoning-“gone” is the word he uses – lost in a creative flow that he can barely recall afterwards.

Wordlessly, the 43-yer-old Everhart explodes into dervish of frenetic motion, cranking up Brahms’s Symphony No.4 to a deafening decibel and attacking the canvas. He whuumps it with a hardware-store paint roller, as if he were beating a rug; savagely squiggles it with his fingerprints; smears it what the sleeve of his black turtleneck. Stray droplets of purple sail onto the ceiling and floor. Everhart is zoning-“gone” is the word he uses – lost in a creative flow that he can barely recall afterwards. What people can’t get enough of, especially with Snoopy’s 50th anniversary in the year 2000, are Everhart’s colossal paintings. Museum-goers, art connoisseurs, and international dealers are all clamoring for Everhart’s art lite. His Peanuts paintings have hung in the Louvre, in museums from Milan to Minneapolis, and in Japan – where comics are a cultural obsession – they just finished a hugely popular run at Osaka’s National Museum of Modern Art. Collectors are willing to shell out $35,000 to own an original Everhart, and when his more-affordable lithographs were hawked on QVC last year for $1,000 each, more than 100 sold in five minutes. Plus, Everhart’s work will soon be gracing two new HarperCollins coffee-table books: a hefty Snoopy biography due out this fall, and, come spring, a glossy pictorial with foldout pages, devoted solely to Everhart’s Peanuts paintings.

What people can’t get enough of, especially with Snoopy’s 50th anniversary in the year 2000, are Everhart’s colossal paintings. Museum-goers, art connoisseurs, and international dealers are all clamoring for Everhart’s art lite. His Peanuts paintings have hung in the Louvre, in museums from Milan to Minneapolis, and in Japan – where comics are a cultural obsession – they just finished a hugely popular run at Osaka’s National Museum of Modern Art. Collectors are willing to shell out $35,000 to own an original Everhart, and when his more-affordable lithographs were hawked on QVC last year for $1,000 each, more than 100 sold in five minutes. Plus, Everhart’s work will soon be gracing two new HarperCollins coffee-table books: a hefty Snoopy biography due out this fall, and, come spring, a glossy pictorial with foldout pages, devoted solely to Everhart’s Peanuts paintings.  It was wacky, but if he didn’t have long to live...why not abandon his lucrative landscapes and concentrate fulltime on these Peanuts paintings? His art would match his outlook on life: He would take seriously the pursuit of not taking things seriously. Since then, his cancer has been in remission and his career is in overdrive. “Ever since I was diagnosed," Everhart recalls of his illness, “everything in my life has completely changed.

It was wacky, but if he didn’t have long to live...why not abandon his lucrative landscapes and concentrate fulltime on these Peanuts paintings? His art would match his outlook on life: He would take seriously the pursuit of not taking things seriously. Since then, his cancer has been in remission and his career is in overdrive. “Ever since I was diagnosed," Everhart recalls of his illness, “everything in my life has completely changed.